by Alana Flowers | Jan 10, 2018 | Kinloch Related

I know I know. It’s been a while since I’ve updated the site on what’s been going on with The Kinloch Doc. Life just continues to happen and move faster than anticipated. Such is my life. But all is well. While the production side hasn’t moved as swiftly as I hoped...

by Alana Flowers | Sep 19, 2017 | Kinloch Related

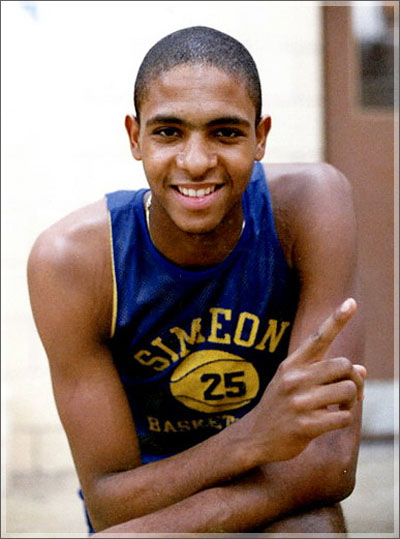

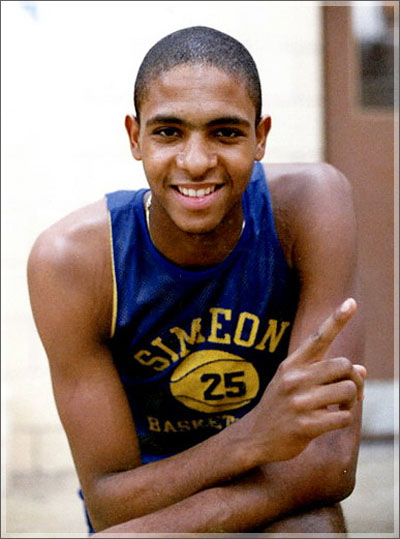

In October of 2012, I got hip to the ESPN series titled 30 for 30: a number of documentary films highlighting significant people and events in sports history. This specific film was about Ben “Benji” Wilson, Chicago’s #1 high school basketball player gunned down one...

by Alana Flowers | Aug 31, 2017 | Kinloch Related

One thing you will always see me write about in these posts is PURPOSE and what I experienced today is another affirmation of just that. This afternoon, I had a pre-scheduled meeting with Justine Blue (Kinloch’s City Manager) as a follow-up from our previous...

by Alana Flowers | Aug 28, 2017 | Kinloch Related

There’s been a large gap in time between my last director daily but trust and believe, a lot has been going on with the documentary. Since July, I have been working more on the Kinloch site, launched the Kinloch IG and Facebook page, celebrated my 27th birthday...

by Alana Flowers | Aug 20, 2017 | Kinloch Related

This past Friday was completely dedicated to Kinloch. During my lunch break, I met with Emma Riley, another Wash U alum and producer/director of Displaced – a short film about the erasure of Blacks in the City Clayton, MO. One of my professors sent me the link...

by Alana Flowers | Aug 20, 2017 | Kinloch Related

This morning I met with Justine Blue: City Manager of Kinloch. I learned her maiden name is Wells and we are apparently some “kin” to each other, which is of no surprise to me. The conversation with her was beyond fruitful – more than I anticipated...

by Alana Flowers | Aug 20, 2017 | Kinloch Related

I spent my entire evening playing around with the Kinloch website. It was my first time viewing the site again since we first purchased the domain last month and I see that Devin has been putting in a lot of hours. I created the template for the “Kinloch...

by Alana Flowers | Aug 20, 2017 | Kinloch Related

My Aunt Violet, another Kinlochian (as I’ve heard it called) passed away today. That now makes both of my Grandparents, Uncle Pee Wee, Aunt April, Uncle Russell, and now her. My father is the last surviving sibling from grandparents. However, I have two...

by Alana Flowers | Aug 20, 2017 | Kinloch Related

I reached out to Dan Parris, the Executive Producer and Director of the film Show Me Democracy. I learned that his film actually features the center the organization I work for: St. Louis Graduates High School to College Center. I sent him a list of questions that I...

by Emily Scates | Aug 4, 2017 | Kinloch Related

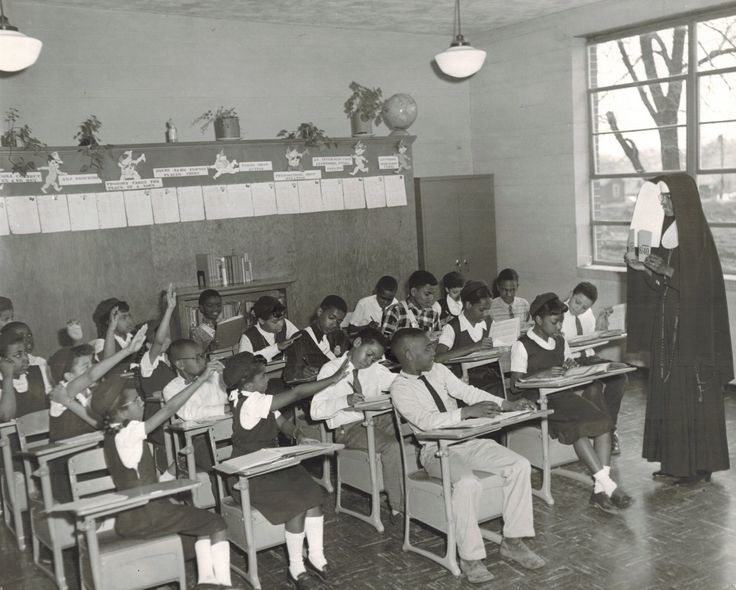

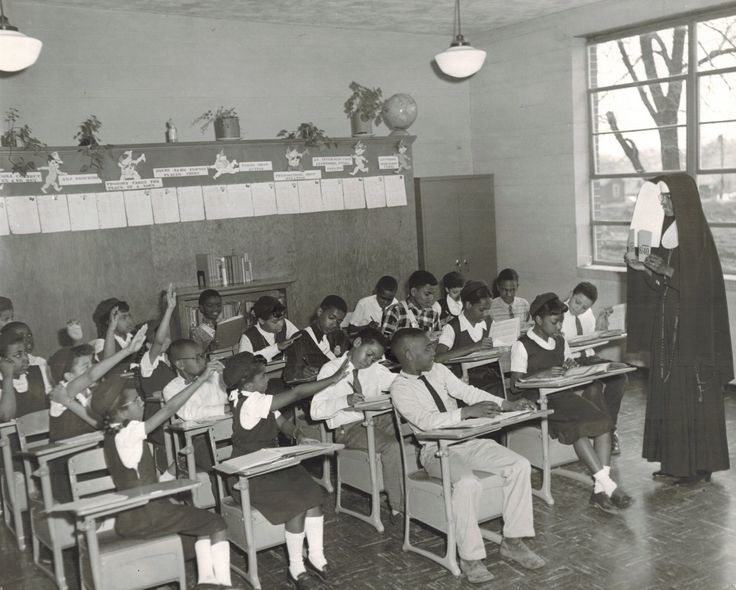

The playground was concrete. In the 1990s, the all-black Catholic school, which nested within a once-flourishing farming community, now had no vegetation in sight except for the grass within the gated yard of the rectory where the white priest stayed. At recess,...